The Amazon map is more than a geographical tool—it’s a gateway into the heart of the world’s largest rainforest and one of the most critical ecosystems on Earth. Stretching across nine South American countries, the Amazon Basin finds its greatest expression in Brazil and Peru, which together encompass a vast portion of the forest’s territory and biodiversity. By tracing the natural and political boundaries of these two countries, we gain a deeper understanding of the Amazon’s ecological fabric and the challenges of preserving it.

Mapping the Amazon River: From Peru to Brazil

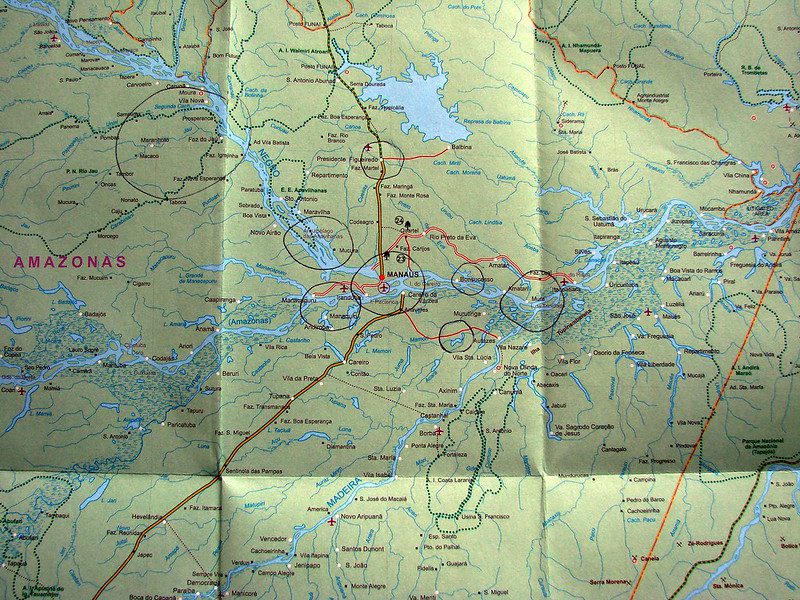

The Amazon River, the lifeblood of the rainforest, begins its long journey high in the Andes of southern Peru. As the river descends and gathers force, it defines Peru’s eastern wilderness before flowing into Brazil—where it becomes the most voluminous river system on Earth, stretching over 6,400 kilometers to the Atlantic Ocean. This river crosses the border and transforms into a colossal hydrological network, visible on every detailed Amazon map.

One of the most striking cross-border features is the “Encontro das Águas” in Brazil, where the dark Rio Negro and sandy Rio Solimões meet near Manaus. Though originating in Peru, the river’s identity as the Amazon is most prominently mapped within Brazilian territory, where it expands into a web of over 1,100 tributaries. Maps also reveal the presence of the Hamza River, a subterranean flow mirroring the Amazon’s route beneath Brazil—an underground enigma that may even stretch into Peruvian soil.

Borders of Biodiversity: Brazil and Peru in the Amazon

Geographically, Brazil contains roughly 60% of the Amazon Rainforest, making it the country most associated with the region. Yet Peru holds the second-largest share, with about 13% of the Amazon within its borders. These two nations anchor much of the basin’s ecological and cultural wealth. Mapping their respective Amazonian territories reveals striking contrasts and overlaps in flora, fauna, and human habitation.

Brazil’s Amazon, mapped in vast green swathes, includes major conservation units such as the Jaú National Park and indigenous territories where deforestation pressures are high. In contrast, Peru’s Amazon, while less deforested, is home to more remote and ecologically intact regions like Manu National Park and Pacaya-Samiria Reserve—biodiversity hotspots that lie far from industrial encroachment. Mapping these regions is essential for conservation strategies that respect both ecological integrity and indigenous sovereignty.

The Amazon on a World Map: A Transnational Lifeline

On a global scale, maps of the Amazon show Brazil and Peru as central players in the climate system. Together, their forests drive the “biotic pump”, a theory suggesting that tree-generated water vapor creates atmospheric pressure gradients that pull moist air inland, shaping rainfall patterns across South America and even influencing weather on other continents.

Maps also reveal how species distribution ignores political borders. Jaguars, harpy eagles, and pink river dolphins roam freely between Brazil and Peru, making cross-border ecological mapping vital for wildlife conservation. Likewise, indigenous cultures such as the Shipibo-Conibo of Peru and the Yanomami of Brazil share knowledge systems rooted in a forest that transcends lines on a map.